Nap Lajoie

| Nap Lajoie | |

|---|---|

Lajoie in 1913 | |

| Second baseman / Manager | |

| Born: September 5, 1874 Woonsocket, Rhode Island, U.S. | |

| Died: February 7, 1959 (aged 84) Daytona Beach, Florida, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| August 12, 1896, for the Philadelphia Phillies | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 26, 1916, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .339 |

| Hits | 3,252 |

| Home runs | 82 |

| Runs batted in | 1,599 |

| Managerial record | 377–309 |

| Winning % | .550 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

As player

As manager | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

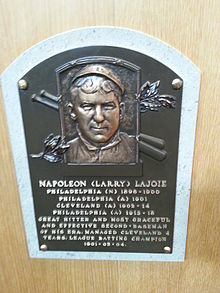

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1937 |

| Vote | 83.6% (second ballot) |

Napoléon "Nap" Lajoie (/ˈlæʒəweɪ/; September 5, 1874 – February 7, 1959), also known as Larry Lajoie, was an American professional baseball second baseman who played 21 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). Nicknamed "the Frenchman", he represented both Philadelphia franchises and the Cleveland Naps, the latter of which he became the namesake of, and from 1905 through 1909, the player-manager.

Lajoie was signed to the Philadelphia Phillies of the National League (NL) in 1896. By the beginning of the 20th century, however, the upstart American League (AL) was looking to rival the supremacy of the NL and in 1901, Lajoie and dozens of former National League players joined the American League. National League clubs contested the legality of contracts signed by players who jumped to the other league, but eventually Lajoie was allowed to play for Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics. During the season, Lajoie set the all-time American League single-season mark for the highest batting average (.426).[1][2][3][self-published source]: p.76 [4]: p.88 One year later, Lajoie went to the Cleveland Bronchos, where he would play until the 1915 season, when he returned to play for Mack and the Athletics. While with Cleveland, Lajoie's popularity led to locals electing to change the club's team name from Bronchos to Napoleons ("Naps" for short), which remained until after Lajoie departed Cleveland and the name was changed to Indians (the team's name until 2021).

Lajoie led the AL in batting average five times in his career and four times recorded the highest number of hits. During several of those years with the Naps, he and Ty Cobb dominated AL hitting categories and traded batting titles with each other, most notably in 1910, when the league's batting champion was not decided until well after the last game of the season and after an investigation by American League President Ban Johnson. Lajoie in 1914 joined Cap Anson and Honus Wagner as the only major league players to record 3,000 career hits. He led the NL or AL in putouts five times in his career and in assists three times. He has been called "the best second baseman in the history of baseball" and "the most outstanding player to wear a Cleveland uniform."[5]: p.207 [6] Cy Young said, "Lajoie was one of the most rugged players I ever faced. He'd take your leg off with a line drive, turn the third baseman around like a swinging door and powder the hand of the left fielder."[4]: p.86 He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937.

Early life

[edit]Lajoie was born on September 5, 1874, in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, to Jean Baptiste and Celina Guertin Lajoie. Jean Lajoie was French-Canadian and had immigrated to the United States. Upon arrival to the U.S., he first settled in Rutland, Vermont, but then moved to Woonsocket, where Nap, the youngest of eight surviving children, was born.[7] Throughout his childhood Lajoie received little formal education.[8]

Jean, who worked as a teamster and laborer, died not long into Lajoie's childhood, which forced him and his siblings to work to support the family.[9]: p.39 Lajoie dropped out of school to work in a textile mill. He also began playing semi-professional baseball for the local Woonsocket team, under the alias "Sandy" because his parents did not approve of their son playing baseball. He earned money as a taxi driver with a horse and buggy and locally was called "Slugging Cabby."[4]: p.88 [9]: p.40 "When I told my father I had decided to take the job he was very angry. He shouted that ball players were bums and that nobody respected them, but I was determined to give it a try at least one season," Lajoie later said.[10] He also received the nickname "Larry" from a teammate who had trouble pronouncing Lajoie.[10] Lajoie admired baseball players such as King Kelly and Charles Radbourn.[11]: p.179

When word of Lajoie's baseball ability spread, he began to play for other semi-professional teams at $2 to $5 per game ($73 to $183 in current dollar terms). He also worked as a teamster.[7] He left Woonsocket and his $7.50 per week ($275 in current dollar terms) working as a taxi driver and joined the Class B New England League's Fall River Indians in 1896. Lajoie played as a center fielder, first baseman and catcher, earning $25 weekly ($916 in current dollar terms).[9]: p.40 [12]: p.19 He recorded 163 hits in 80 games and led the team in batting average, doubles, triples, home runs and hits.[13] Lajoie was "widely regarded as an outstanding prospect," and Indians owner Charlie Marston rejected an offer from the Pittsburgh Pirates for Lajoie in exchange for $500 ($18,312 in current dollar terms). He was also scouted by the Philadelphia Phillies and Boston Beaneaters.[12]: p.19

Major league career

[edit]Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]The Philadelphia Phillies of the MLB's National League (NL) purchased Lajoie and teammate Phil Geier from Fall River for $1,500 ($54,936 in current dollar terms) on August 9. Phillies' manager Billy Nash originally went to Fall River intending to sign Geier only but obtained Lajoie when the team agreed to include him in their asking price.[14][15]: p.55 Author David Jordan wrote:

A legend later grew up that Geier was the main target of Nash's pursuit and that Marston "threw in" Lajoie in order to get the Phillies to pay the $1,500 asking price. This is hardly likely. While Geier was considered a good prospect, Lajoie was banging the ball at a .429 clip in his first professional season, was a fine fielder, and had already been sought by several big league clubs. Nap Lajoie clearly represented a financial asset to Marston, who did not give him away. The price the Phillies paid was a substantial sum for two minor leaguers in 1896.[12]: p.19

Against the Washington Senators on August 12, 1896, Lajoie made his major league debut. He played first base and recorded a single.[12]: p.19 Ed Delahanty was being considered to play the first base position after Dan Brouthers retired. Delahanty, however, wanted Lajoie to play first so he could return to his natural position of left field. Delahanty said to Lajoie, "Look, sonny, you tell the boss you're a first baseman and you and me are gonna get along."[10] Lajoie became the team's first baseman, and by the end of the season he and Delahanty were roommates. Later in 1898, new manager George Stallings moved Lajoie to second base, commenting, "[Lajoie would] have made good no matter where I positioned him."[7]

Lajoie hit .363 and led the NL in slugging percentage in 1897 and doubles and RBIs in 1898.[12]: p.20 [16][17] He had a .378 batting average in 1899, though he played only 77 games due to an injury.[1] In 1900, he missed five weeks due to a broken thumb suffered in a fistfight with teammate Elmer Flick.[7][18]

In April 1900, Brooklyn manager Ned Hanlon made a public offer of $10,000 to purchase Lajoie from the Phillies which would be rebuffed by the Phillies owners.[19]

John Rogers, described as a "penny-pinching" majority owner of the Phillies, assured Lajoie that he would make the same salary as Delahanty.[20] However, Lajoie discovered that while he was earning $2,600 ($95,222 in current dollar terms), Delahanty earned $3,000 ($109,872 in current dollar terms) (contracts for NL players were not allowed to surpass $2,400).[4]: p.88 [21]: p.16 Rogers increased Lajoie's pay by $200 but the damage had already been done. "Because I felt I had been cheated, I was determined to listen to any reasonable American League offer," Lajoie said.[22]: p.96

Philadelphia Athletics

[edit]In 1901, the newly created American League had attracted several of the top players in the competing National League to join its ranks. Rogers declined Lajoie's request for an increase in salary, and as a result Lajoie jumped to the crosstown Philadelphia Athletics, owned by former Phillies' part-owner Benjamin Shibe and managed by Connie Mack.[7] Frank Hough offered Lajoie the contract on behalf of Mack. "Hough offered me $24,000 ($878,976 in current dollar terms) for four years. You can bet I signed in a hurry," Lajoie said.[22]: p.97 Lajoie was considered "the first superstar" to join the newly formed AL. He was also the first player whose yearly salary was $4,000 ($146,496 in current dollar terms).[4]: p.88 [11]: p.180 [23]: p.42 "The Phillies opened their season and drew 6,000 fans. A week later, when we opened, there were 16,000 in the stands. The American League was here to stay," Lajoie later said.[10] Lajoie's batting average that year was .426 (due to a transcription error that was not discovered until 1954, which inaccurately gave his hit total as 220 instead of 229, it was originally recorded at .405, later changed to .422, before finally being revised again to .426).[2][3]: p.76 [4]: p.88 The batting average mark became the all-time AL record after the number was revised. Previously, Ty Cobb and George Sisler had been credited with having the AL's all-time mark.[24] That same year in a game against the Chicago White Sox's Clark Griffith, Lajoie became the second Major Leaguer after Abner Dalrymple in 1881 to be intentionally walked with the bases loaded in an 11–7 game.[11]: p.179 For the 1901 season, Lajoie led the majors in doubles (48), and led the majors in hits (232), batting average (.426), runs (145), on-base (.463) and slugging percentage (.643), and total bases (350). His 125 RBIs led the AL and his 14 home runs were a career-best and his 48 doubles are a Philadelphia Athletics' record.[1][25][self-published source]: p.341 Mack said of Lajoie, "He plays so naturally and so easily it looks like lack of effort."[7] Author Robert Kelly writes:

The .422 [sic] batting average of Lajoie still stands as an AL record. To some degree, however, it is tainted. The 1901 season was the first for the AL and the level of competition was presumably evolving. Such questions, however, in no way cast doubt on the extraordinary batting ability of the second baseman."[26]

In April 1902, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania overruled an earlier decision by the Court of Common Pleas and upheld the reserve clause in contracts between players and NL clubs. President of the Chicago National League Club Jim Hart said the state Supreme Court's decision had dealt "a fatal blow to the rival league" and NL clubs "have won a great victory."[27] The Phillies' Rogers obtained an injunction barring Lajoie from playing baseball for any team other than his team.[28] However, a lawyer discovered that the injunction was enforceable only in the state of Pennsylvania. The courts ruled that the reserve clause was not valid for players who signed with an AL team.[29] Mack responded by trading Lajoie and Bill Bernhard to the then-moribund Cleveland Bronchos, whose owner, Charles Somers, had provided considerable financial assistance to the A's in the early years.[30][31][32]: p.36 Lajoie was also pursued by Charles Comiskey, owner of the Chicago White Sox.[33]

Cleveland Bronchos/Naps

[edit]

Lajoie, nicknamed "The Frenchman" and considered baseball's most famous player at the time, arrived in Cleveland on June 4; his play was immediately met with approval from fans.[9]: p.41 [15]: p.55 [25]: p.17 The Bronchos drew 10,000 fans to League Park in Lajoie's first game.[5]: p.12 [10] The Bronchos' record at the time Lajoie and fellow Athletics teammate, Bill Bernhard, joined was 11–24 and improved to 12–24 after the team's inaugural game with their new players, a 4–3 win over the Boston Americans.[5]: p.13 [34] The team went on to finish 69–67, fifth in the AL, for the franchise's first winning record since the AL began as a league.[35][36] After his first season with the Bronchos, Lajoie's .378 average led all AL players.[37] New York Giants manager, John McGraw, was rumored to want to sign Lajoie, but Lajoie said "... I intend to stick to Cleveland."[38]

For the remainder of 1902 and most of 1903, Lajoie and Elmer Flick traveled separately from the rest of the team, needing to avoid entering Pennsylvania so as to avoid a subpoena (the only team they could legally play with inside state limits was the Phillies). When the Naps (the team was temporarily named the Naps after Nap Lajoie) went to play in Philadelphia, Lajoie and Bernhard would go to nearby Atlantic City to help pass the time.[32]: p.36 The issue was finally resolved when the leagues made peace through the National Agreement in September 1903 (which also brought the formation of the World Series).[5]: p.13 [9]: p.40 To begin the 1903 season, the club changed its name from the Bronchos to the Naps in honor of Lajoie after a readers' poll result was released by the Cleveland Press.[5]: p.13 (The team was officially the Blues in their inaugural AL season but changed to the Bronchos for the 1902 season.)[36] The Bronchos finished the season 77–63 and Lajoie finished his first full season with the club again the AL's batting champion with a .344 average.[36] He also led the league in slugging percentage (.518), finished second in doubles (41), third in RBIs (93) and tied for fifth in home runs (7).[39] In the off-season he contracted pleurisy.[10]

During the 1904 season, Lajoie received a suspension after he spat tobacco juice in an umpire's eye.[9]: p.41 He later informally replaced Bill Armour as the team's manager (Armour submitted his resignation on September 9 but as team captain, Lajoie had already been acting as the Naps' field manager). After the season had concluded, Lajoie was officially named manager.[5]: p.14 He still managed to lead the majors with a .376 batting average as he recorded his second consecutive league batting title.[1] He also led the majors in hits (208), doubles (49), RBIs (102) and slugging percentage (.546).[1] Lajoie forbade his players from card playing and gambling during the regular season.[23]: p.107 As a manager, Lajoie was also described as "much too lenient with his players."[22]: p.98

Lajoie contracted sepsis from an untreated spike injury after a game in July 1905.[32]: p.63 Dye from Lajoie's stockings entered his bloodstream and led to blood poisoning.[40]: p.48 (A rule was put into place requiring white socks to be worn underneath a player's colored socks.)[41]: p.339 The injury worsened and Lajoie eventually came to games in a wheelchair, and doctors considered amputation.[21]: p.32 The injury and illness kept Lajoie out until August 28, when he returned as the team's first baseman. Near the end of the season he sustained an injury to his ankle from a foul tip during an at bat, and did not play for the remainder of the season but continued to manage from the bench.[5]: p.14 He finished the season having only appeared in 65 games (a career-low, other than his rookie season when he was not called up until well after the season had begun).[1] The Naps finished with a 76–78 record in a season in which they had been 52–29, and held a three-game lead in the American League on July 24[36] Baseball historian Bill James wrote of Lajoie's higher-than-normal career putout total and importance to Cleveland:

Nap Lajoie was not only the team's superstar, after 1905 he was also the manager. He was more than that—hell, the team was actually called the "Naps" in his honor, as if Lajoie was the team. If Lajoie was in the habit of covering second base every play, the shortstop certainly wasn't going to tell him not to.[42]: p.489

Lajoie led the majors in 1906 in hits (214) and doubles (48) and the Naps finished third in the AL again with a winning record, 89–64.[1][43] Lajoie finished second in the AL to George Stone in batting average, slugging and on-base percentage.[44] In 1906 he married Myrtle Smith and the couple moved to a small farm outside Cleveland.[9]: p.41

In June of the 1907 season, Lajoie's .296 average, "an average even now that scores of players would be glad to accept,"[45] put him at risk for hitting below .300 for the first time in his career. He also missed 15 games due to a recurrence of sepsis.[5]: p.15 Lajoie and Naps first baseman George Stovall got into an argument in a hotel lobby and Stovall broke a chair over Lajoie's head. "George didn't mean anything by it," Lajoie said, and the two maintained a working relationship.[15]: p.57 [22]: p.98 He finished the season with an average of .301.[1] Naps owner Charles Somers received a trade offer from the Detroit Tigers for Flick and the Tigers' Ty Cobb. Tigers manager Hughie Jennings called Somers and told him he was offering the trade because Cobb was not getting along with several teammates. Somers decided to retain Flick, saying, "We'll keep Flick. Maybe he isn't as good a batter as Cobb, but he's much nicer to have on the team."[5]: p.16 The Naps finished the regular season in second place to the Tigers with a 90–64 record, a half-game behind the Tigers (who finished 90–63 and were not forced to make-up a rained out game in accordance with league rules).[5]: p.16 Lajoie was partly blamed for the Naps' second-place finish. Author Fred McMane described an instance during the season between Naps catcher Nig Clarke and Lajoie.

Clarke ... was newly married and asked Lajoie for a day off so that he could go home. Lajoie refused. Clarke sulked and walked over to warm up pitcher Addie Joss. On the first pitch, he stuck out a finger and the ball broke it cleanly. With blood streaming from his hand, Clarke waved it defiantly in front of Lajoie. "Now can I go home?" asked Clarke. He was out five weeks, and Cleveland lost the pennant to Detroit by half a game.[22]: p.98–99

Lajoie finished the season tied for third-most in hits (168) while Cobb's batting average, slugging and on-base percentages, and hit total led the American League.[46] Baseball historians have suggested the managerial duties Lajoie took on affected his offensive numbers.[23]: p.42

Lajoie's dissatisfaction with the Naps' play worsened. "You can't win in the major leagues unless you have players who know the game. We don't have time to teach and train youngsters up here. Our job is to win pennants, not run schools," he said.[40]: p.65 Franklin Lewis, sports writer and author, wrote "Lajoie, in spite of his marvelous fielding and tremendous batting, was not exactly a darling of the grandstand as a manager."[40]: p.52 Lajoie recommended to Somers on August 17, 1909, he find the team a new manager, although he wanted to remain on the club as a player. Somers responded to Lajoie by giving him more time to finalize his decision but when Lajoie came back days later and announced the same decision, Somers acted quickly to find a replacement. Lajoie later described the decision to take on the added duties as a player-manager as the biggest mistake of his career as he felt it negatively affected his play.[10] The highest-paid player in the league, he also offered a $10,000 ($339,111 in current dollar terms) reduction in salary. Somers promoted Naps coach Deacon "Jim" McGuire to manager.[5]: p.17 The team finished 71–82 while Lajoie's .324 average was third in the AL and 33 doubles second.[47] The Naps finished 1910 71–81 but Lajoie had one of his better seasons statistically as he led the majors with a .384 average[a] and 227 hits, both categories bettered only in Lajoie's 1901 campaign.[48][49] His 51 doubles, a career-high, and 304 total bases led the majors, the fourth and final time in his career he would lead the majors in the latter category.[1] Lajoie missed significant parts of back-to-back seasons, the first in 1911 when he appeared in just 90 games.[1][50] Stovall, the former Naps first baseman, replaced McGuire as the club's manager and the Naps finished 80–73.[5]: p.19 Lajoie was forced to sit out six weeks of the 1912 season when he sprained his back in May during a practice session in Chicago.[51] He played in 117 games on the season, an increase of the 90 he played in one season before, but Cleveland, who had hired Joe Birmingham as the team's fifth manager since Lajoie gave up the role in 1909, finished 75–78.[1][5]: p.19 Lajoie and Joe Jackson tied for the team lead with 90 RBIs.[5]: p.20 He finished fourth in the AL with a .368 batting average.[52] In 1913, Birmingham and Lajoie had arguments in the open, including one incident in June when Lajoie cursed Birmingham openly to reporters after being benched during a batting slump.[5]: p.20 Lajoie hit .335 on the year, the last time he would hit over .300 in his career.[1]

Only two other major league players had attained 3,000 career hits until Lajoie hit a double on September 27, 1914, and so joined Cap Anson and Honus Wagner in the 3,000 hit club.[3]: p.77 [14] Lajoie recorded the hit off Yankees pitcher Marty McHale in a 5–3 Naps win.[5]: p.22 [53] His .258 batting average for the season, however, was the lowest since he had joined the majors in 1896.[1] The Naps finished in last place in the American League standings with a 51–102 record, their worst record since joining the league and the franchise's lowest winning percentage (.333).[54] Lajoie requested that Somers trade him and the club obliged, selling Lajoie to the Athletics for the waiver price and in so doing, Lajoie returned to Philadelphia.[5]: p.22 [40]: p.74

Philadelphia Athletics (second stint)

[edit]The following season, 1915, Lajoie returned to the Athletics when Mack signed him to a contract.[14] In his first season back with the Athletics, he finished with a .280 batting average but the team ended the season in last place with a 43–109 record.[1][55] The 1916 season would be Lajoie's last in the majors. In his final major league game, he hit a triple to help Athletics pitcher Joe Bush win his no-hitter.[22]: p.100 Lajoie, aged 41 years, played in 113 games and finished with a .246 average.[1] Philadelphia's season record was worse than the previous season's franchise-low record, and the team finished in last place again with a 36–117 record.[56] The Athletics' winning percentage (.235) is the franchise's worst winning percentage (through the 2021 season); moreover, it is the lowest of any major league team in the modern (post-1900) era.[57][58]: p.105

Minor leagues and retirement

[edit]In 1917, Lajoie joined the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League as manager. At the age of 42, Lajoie won the league's batting title with batting average of .380. He appeared in 151 of 156 games and, for the first time in his career, played on a team that won a pennant.[22]: p.100 He later was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers for $3,000 ($60,770 in current dollar terms) in March 1918 but the contract was annulled by the Commissioner's office and made a free agent to which Lajoie was "well pleased".[59][60] Later that same year he joined the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association as player-manager. He helped lead the team to a third-place finish but the season was impacted due to the U.S.'s involvement in World War I. Lajoie made his services available to the draft board but they rejected his offer.[9]: p.43 On December 27, 1918, Lajoie announced his retirement from baseball.[22]: p.101 [61]

Several years after his retirement, a story in The Milwaukee Sentinel talked of Lajoie's ability to "outguess any pitcher." Lajoie faced pitcher Red Donahue, who avoided pitching fastballs to Lajoie after seeing him go 4-for-4 against a fellow pitcher. Donahue instead made pitches on the outside corner, to which Lajoie reached over "and hit them with ease."[62] Donahue then aimed a pitch at Lajoie's head and he proceeded to hit a home run. "That's the kind I eat", he said.[62]

Managerial record

[edit]| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| CLE | 1905 | 0 | 37 | 21 | .638 | 5th in AL | – | – | – | |

| 55 | 19 | 36 | .345 | |||||||

| CLE | 1906 | 153 | 89 | 64 | .582 | 3rd in AL | – | – | – | |

| CLE | 1907 | 152 | 85 | 67 | .559 | 4th in AL | – | – | – | |

| CLE | 1908 | 154 | 90 | 64 | .584 | 2nd in AL | – | – | – | |

| CLE | 1909 | 114 | 57 | 57 | .500 | Reassigned | – | – | – | |

| Total[63] | 686 | 377 | 309 | .550 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

Rivalry with Ty Cobb

[edit]

For the first part of the 20th century, Lajoie's and Ty Cobb's statistics rivaled each other like few other players in the American League.[58]: p.10 In 1908, Honus Wagner and Lajoie recorded their 2,000th career hits. Baseball historian David Anderson wrote:

Nap Lajoie reached the milestone later in the summer with even less hoopla, in an age when individual records received little attention from the press and were generally scorned by many players. Players overly worried about their individual stats were often unpopular with teammates. The modesty of Wagner and Lajoie over their achievements contrasted sharply with Cobb's ambition and overriding interest in his individual numbers.[23]: p.132

The Lajoie-Cobb rivalry reached a peak in 1910, when Hugh Chalmers of the Chalmers Auto Company (a direct predecessor to modern-day Chrysler) promised a Chalmers 30 Roadster to the season's batting champion.[64] The public became fascinated with the daily statistics of Lajoie and Cobb in what became known as the Chalmers Race. Sports bettors, who by this time followed the sport attentively, also followed the daily reports with interest. Cobb took the final two games, a doubleheader, off against the Chicago White Sox, confident that his average was safe and would allow him to win the AL batting title—unless Lajoie had a near-perfect final day. Going into the final game of the season, Cobb's average led Lajoie's, .383 to .376.[65]

Lajoie and the Naps faced a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns in Sportsman's Park, Cleveland's final two games of the season. After a sun-hindered fly ball went for a stand-up triple and another batted ball landed for a cleanly hit single, Lajoie had five subsequent hits – bunt singles dropped in front of rookie third baseman Red Corriden (whose normal position was shortstop), who was playing closer to shallow left field on orders, it has been suggested, of manager Jack O'Connor.[66] In his final at bat of the second game, Lajoie reached base on another bunt but the throw to first by Corriden was off target and the play was scored a error and thus, Lajoie did not record an official at-bat, nor a hit.[67] He finished the doubleheader 8-for-8 and his batting average increased to .384, .001 greater than Cobb's mark. Although the AL office had not officially announced the results, Lajoie began to receive congratulations from fans and players, including eight of Cobb's Detroit Tigers teammates. Most players in the league preferred Lajoie's personality to that of Cobb's.[32]: p.124 Coach Harry Howell is reported to have said to the game's official scorer, E. V. Parish, "to do well by Lajoie."[64] Howell was reported to have offered a bribe to Parish, which as described in Al Stump's biography of Cobb, was a $40 ($1,263 in current dollar terms) suit. Parish refused the offer and the resulting uproar ended in O'Connor and Howell being banned from the major leagues by AL President Ban Johnson.

Johnson had the matter investigated, and after having Cobb's September 24 doubleheader statistics re-checked, discovered only the first game of Cobb's statistics had been scored, but not the second game, in which he went 2-for-3. This put Cobb's suggested actual batting average at .385, again ahead of Lajoie's. In the end, Johnson ruled that Lajoie's sacrifice bunt should have been recorded as a hit (which would have allowed him to go 9-for-9) but that Cobb's batting average was greater, recording 196 hits in 509 at bats to Lajoie's 227 hits in 591 at bats.[64] Johnson asked Chalmers if his company would award an automobile to each player, to which he agreed. Lajoie initially refused the car, but eventually relented and accepted it.[66] Cobb said, "I am glad that I won an automobile and am especially pleased that Lajoie also gets one. I have no one to criticize. I know the games were on the square and I am greatly pleased to know that the affair has ended so nicely."[32]: p.125 Lajoie said, "I am quite satisfied that I was treated fairly in every way by President Johnson, but I think the scorer at St. Louis made an error in not crediting me with nine hits. However, I am glad that the controversy is over. I have the greatest respect for Cobb as a batter and am glad of his success."[32]: p.125

The Sporting News published an article written by Paul MacFarlane in its April 18, 1981, issue where historian Pete Palmer had discovered that while Cobb's September 24 doubleheader was not correctly tabulated (perhaps purposely) according to the correct date, the second game's statistics were in fact included in the next day's ledger, thus incorrectly recording a second 2-for-3 performance from Cobb which meant Lajoie's average was greater.[64][68][69] Author James Vail wrote in 2001:

To date, it seems that no one knows for certain who won that 1910 batting title. Total Baseball, which is now the official major-league record, lists both men at .384 in its seasonal section, but its player register has Lajoie at the same number and Cobb at .383—so even the various editors of that source do not, or cannot, agree.[70]

Jon Wertheim wrote in Sports Illustrated 100 years after the event,

The statistics for the Detroit players had been crossed out and nullified. Every Detroit player, that is, except one: Ty Cobb. It takes something less than a detective to arrive at the conclusion that at some point Johnson (or someone in the league office, anyway) realized the error and decided to conceal it.[64]

Legacy

[edit]

Lajoie ended his career with a lifetime .338 batting average. His career total of 3,252 hits was the second-most in MLB history at the time of his retirement, behind only Honus Wagner's total (3,420). Lajoie's 2,522 hits in the American League was that league's record until Cobb surpassed his mark.[71] He was among the second group of players elected to the Hall of Fame in 1937 and was later inducted on June 12, 1939, when the Hall opened that same year.[72] Lajoie obtained the greatest number of votes as he led induction mates Tris Speaker (165 votes) and Cy Young (153) with 168 votes (83.6 percent of ballots) from the Baseball Writers' Association of America.[73][74] Lajoie led all second basemen in the NL in putouts (1898) and the AL four times in his career (1901, 1903, 1906, and 1908). From 1906–1908 he led the AL in assists (amongst second basemen).[1] He also led the league in double plays six times in his career.[41]: p.339 Baseball historian William McNeil rates Lajoie as the game's greatest second baseman, when combining both offensive and defensive impact.[75] Bill James argues, "In the last 20 years several statistical analysts ... have credited Lajoie with immense defensive value ... this analysis is incorrect. He was a competent fielder, even a good fielder. He was not a defensive superstar."[42]: p.487

During spring training before the 1928 season, Lajoie commented on the 1927 New York Yankees. "Of course, you could see a lot of loafing going on but if that club is the greatest of all times, you just know that we had a lot of clubs in my time who were world champions and didn't know it."[76] He died in Daytona Beach, Florida on February 7, 1959, at the age of 84 from complications associated with pneumonia.[77][78] He had fallen in the autumn of 1958 and fractured his arm.[2] His wife had died earlier in 1951.[10] In 1999, he ranked number 29 on The Sporting News' list of the "100 Greatest Baseball Players", and was a nominee for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[79]

Lajoie was included in the checklist for the 1933 baseball card set produced by the Goudey Gum Company. However, the card (#106 in the set) became infamous for being impossible to find copies of.[80] While the company eventually sent copies of the card to those collectors who wrote in to complain, it was revealed years later that the uncut sheets of the set did not include the card, and the alleged 1933 Lajoie card was printed with the 1934 set. Today, the card is among the highest value from the set.[81]

Lajoie is mentioned in the poem "Line-Up for Yesterday" by Ogden Nash:

L is for Lajoie

Whom Clevelanders love,

Napoleon himself,

With glue in his glove.

— Ogden Nash, Sport magazine (January 1949)[82]

In Ring Lardner's 1911 baseball song, "Gee, It's a Wonderful Game", a stanza refers to Lajoie:

Who lost out in the battle of old Waterloo?/

I don't know, I don't know/ They say 'twas Na-po-le-on/ Maybe it's true/ Maybe so, I don't know/ The pink sheets don't print Mr. Bonaparte's face/ No stories about him today/ 'Cause he never could hold down that old second base/ Like his name sake/

Big Nap Lay'-ooh-way

Lajoie's likeness made a brief cameo appearance in the 1992 The Simpsons episode "Homer at the Bat" as one of the would-be ringers for Mr. Burns' company softball team. Mr. Burns had planned to have Lajoie play second base, until his assistant Smithers points out that all of the players Mr. Burns had selected had long since retired and died.

See also

[edit]- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball runs batted in records

- List of Major League Baseball hit records

- List of Major League Baseball doubles records

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career total bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

- Major League Baseball Triple Crown

Footnotes

[edit]a Major League Baseball has not revised Cobb's batting average, which would then designate Lajoie as the 1910 batting champion. The Sporting News wrote of statistical evidence showing Cobb's 1910 season statistics had been tampered with and he was given two extra base hits but MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn declined to announce Lajoie the winner.[83] Both the Society for American Baseball Research and Baseball-Reference.com list Lajoie as having the higher batting average and thus, the batting champion.[49][84][85]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Nap Lajoie Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Nap Lajoie Breaks Arm In Fall". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. February 21, 1958. p. 9. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c Cressman, Mark (2008). The A-to-Z History of Base Ball. Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4363-2260-7. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Rains, Rob (2004). Rawlings Presents Big Stix: The Greatest Hitters in the History of the Major Leagues. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing. ISBN 1-58261-757-0. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Schneider, Russell (2004). Peter L. Bannon; Joseph J. Bannon, Sr.; Susan M. Moyer (eds.). The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia (Third ed.). Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing. ISBN 1-58261-840-2. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ Corcoran, Cliff (July 22, 2011). "Where does Alomar rank among game's best second basemen?". Si.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Constantelos, Stephen; Jones, David. "Nap Lajoie". sabr.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ Gietshchier, Steven P. (2000). Kirsch, George B.; Harris, Othello; Nolte, Claire E. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Ethnicity and Sports in the United States. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 280. ISBN 0-313-29911-0. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fingers, Rollie; Ritter, Yellowstone (2010). The Rollie Fingers Baseball Bible: Lists and Lore, Stories and Stats. Covington, Kentucky: Clerisy Press. ISBN 978-1-57860-342-8. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Napoleon Lajoie, Indians great". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio: Advance Media. February 7, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c Kalb, Elliot (2005). Who's Better, Who's Best in Baseball?. New York: Mc-Graw Hill. ISBN 0-07-144538-2. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Jordan, David M. (2002). Occasional Glory: The History of the Philadelphia Phillies. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1260-7. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ "1896 Fall River Indians Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Nap Lajoie Out to Make Baseball History; Frenchman One of the Most Popular Players in Game". The Milwaukee Sentinel. January 31, 1915. Retrieved September 12, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Fleitz, David L. (2001). Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3312-4. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ "1897 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ "1898 National League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Maroon, Thomas; Maroon, Margaret; Holbert, Craig (2007). Akron-Canton Baseball Heritage. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 9780738551135. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hanlon Offers $10,000 for Lajoie". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 5, 1900. p. 6.

- ^ Adler, Richard (2008). Mack, McGraw, and the 1913 Baseball Season. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7864-3675-0. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Jordan, David M. (1999). The Athletics of Philadelphia: Connie Mack's White Elephants, 1901–1954. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0620-8. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

nap lajoie.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McMane, Fred (2000). The 3,000-Hit Club. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing. ISBN 9781582612201. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, David W. (2000). More than Merkle: A History of the Best and Most Exciting Season in Human History. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1056-6. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Was the Leader". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. November 18, 1961. p. 20. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Taylor, Ted (2010). The Ultimate Philadelphia Athletics Record Book 1901–1954. Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-4500-2572-0. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ Kelly, Robert E. (2009). Baseball's Offensive Greats of the Deadball Era: Best Producers Rated by Position, 1901–1919. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7864-4125-9. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ "Blow To American League" (PDF). The New York Times. April 22, 1902. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "Baseball Players Enjoined" (PDF). The New York Times. April 24, 1902. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "American League Celebrates 75th Year". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Associated Press. January 30, 1975. p. 3C. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "1902 Cleveland Bronchos Batting, Pitching & Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "Pneumonia Relapse Fatal to Original Hall-of-Famer". The Gadsden Times. Associated Press. February 8, 1959. p. 12. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Cook, William A. (2008). August "Garry" Herrmann: A Baseball Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3073-4. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ "Other Outlaw Clubs Wanted Nap Lajoie". The Pittsburg Press. May 27, 1902. p. 16. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "1902 Cleveland Bronchos Schedule, Box Scores and Splits". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "1902 American League Season Summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Cleveland Indians Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "1902 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Declares He Will Stay With Cleveland". The Pittsburg Press. August 17, 1902. p. 19. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "1903 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Franklin A. (2006). The Cleveland Indians. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-885-2. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Humphreys, Michael A. (2011). Wizardry: Baseball's All-Time Greatest Fielders Revealed. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539776-5. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ a b James, Bill (2003). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-80697-5. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "1906 American League Season Summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "1906 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Is Falling Down". The Pittsburg Press. June 29, 1907. p. 3. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "1908 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "1909 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "1910 American League Season Summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ a b "1910 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "Stars Absent From Game". The Troy Northern Budget. October 1, 1911. p. 13. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Will Be Out For Six Weeks". The Pittsburg Press. May 6, 1912. p. 16. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "1912 American League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Goodman, Rebecca; Brunsman, Barrett J. (2005). This Day in Ohio History. Cincinnati: Emmis Books. p. 293. ISBN 1-57860-191-6. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ "Cleveland Indians Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ "1915 Philadelphia Athletics Batting, Pitching & Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ "1916 Philadelphia Athletics Batting, Pitching & Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ "Oakland Athletics Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Barzilla, Scott (2002). Checks and Imbalances: Competitive Disparity in Major League Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 10. ISBN 0-7864-1255-0. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

nap lajoie retirement.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Will Wield Bat Under Banner of Colonel Ebbets This Year" (PDF). The New York Times. March 23, 1918. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Is Declared Free". The Vindicator. Youngstown, Ohio. April 14, 1918. p. 1C. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Quits Game" (PDF). The New York Times. December 28, 1918. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "Nap Lajoie Could Outguess Hurlers". The Milwaukee Sentinel. July 8, 1923. Retrieved September 12, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Managerial Record". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Wertheim, L. Jon (September 20, 2010). "The Amazing Race". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Queen, Mike (July 11, 2023). "Embarrassing Baseball Scandals Fans Want to Forget". Headlines and Heroes: Newspapers, Comics and More Fine Print [Blog]. Library of Congress. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Manoloff, Dennis (October 8, 2010). "A century doesn't erase questions surrounding Nap Lajoie's 8-for-8 day". Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Cleveland Naps 3, St. Louis Browns 0 (2)". www.retrosheet.org. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ Schwarz, Alan (July 31, 2005). "Numbers Are Cast in Bronze, but Are Not Set in Stone". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ Melody, Tom (April 9, 1986). "A Century Of Figures And Facts The Sporting News Is Still Going Strong". Orlando Sentinel. KNT News Service. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ Vail, James F. (2001). The Road to Cooperstown: A Critical History of Baseball Hall of Fame Selection Process. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 210. ISBN 0-7864-1012-4. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ "Ty Cobb Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie – Induction Speech". Baseballhall.org. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "Three Baseball Greats Selected". Telegraph-Herald. Dubuque, Iowa. January 20, 1937. p. 9. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "1939 Induction Ceremony". Baseballhall.org. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ McNeil, William F. (2009). All-Stars for All Time: A Sabremetric Ranking of the Major League Best, 1876–2007. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-7864-3500-5. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Yanks Failed To Show Much to Nap Lajoie". The Miami News. April 15, 1928. p. 15. Retrieved September 12, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Victim of Pneumonia". The Miami News. Associated Press. February 8, 1959. p. 1C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Nap Lajoie Laid to Rest". The Miami News. United Press International. February 9, 1959. p. 1C. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "Don't Sleep on the 1933 Nap Lajoie". Heritage Auctions Blog. April 27, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ Whaley, Anson (September 19, 2018). "7 Fun Facts About the Nap Lajoie 1933 Goudey Card". Sports Collectors Daily. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "Line-Up for Yesterday by Ogden Nash". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "1910: The Strangest Batting Race". Mlb.com. Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ Ginsburg, Daniel. "Ty Cobb". sabr.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ Gillette, Gary; Spatz, Lyle. "Not Chiseled in Stone: Baseball's Enduring Era and the SABR Era". Retrieved September 16, 2012.

External links

[edit]- Nap Lajoie at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Nap Lajoie managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Nap Lajoie at Find a Grave

- 1874 births

- 1959 deaths

- Baseball players from Rhode Island

- Major League Baseball second basemen

- Philadelphia Phillies players

- Philadelphia Athletics players

- Cleveland Bronchos players

- Cleveland Naps players

- Cleveland Naps managers

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- American League batting champions

- American League home run champions

- American League RBI champions

- American League hitting Triple Crown winners

- National League RBI champions

- 19th-century baseball players

- Fall River Indians players

- Toronto Maple Leafs (International League) players

- Toronto Maple Leafs (International League) managers

- Indianapolis Indians players

- Indianapolis Indians managers

- American taxi drivers

- American people of French-Canadian descent

- People from Woonsocket, Rhode Island

- Major League Baseball player-managers

- American expatriate baseball players in Canada

- Baseball coaches from Rhode Island